Recurring events involving public art have underscored the tension between that expression and the law. Banksy’s “residence” in New York last fall broached this subject, but this summer’s Brooklyn Bridge flag incident, and several new lawsuits asserting copyright in graffiti will test the bounds of what the law protects and what it permits. As Banksy says in one of his murals, "graffiti is a crime."

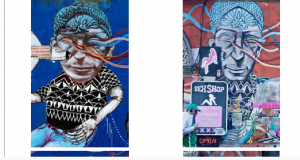

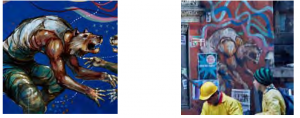

The question is far more than academic. Roberto Cavalli, an Italian fashion designer, is currently facing a lawsuit in California claiming that his designs incorporate a mural in San Francisco’s Mission district by the artists known as Revok, Reyes and Steel. American Eagle clothing faces a claim by Miami street artist David Anasagasti (better known as “Ahol Sniffs Glue”), arguing that his mural “Ocean Grown” was wrongfully included in an advertising campaign. In Chicago, director Terry Gilliam faces a request to enjoin further distribution of his new film Zero Theorem because of the similarity between the background of a part of the movie set, and a graffiti mural in Buenos Aires, Argentina (these comparisons are from the Complaint):

Is all this putting the cart before the horse? Surprisingly, as an article in The Atlantic this month points out, it is far from clear how much courts will recognize copyright in graffiti in the first instance. While I certainly agree with Philippa Loengard (assistant director of Columbia Law School’s Kernochan Center for Law, Media, and the Arts) that the American Eagle infringement seems pretty clear, one really never knows until a court weighs in. If that needed a reminder, the remarkable amicus brief filed this month with the Supreme Court about rap lyrics and free speech underscores it. Remember: photographs are copyrighted as a matter of course now, but once upon a time it took a Supreme Court case (Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony) to establish the principle; before that, people weren’t entirely sure. If the Supreme Court needs an explanation about rap music and threats, perhaps it would consider graffiti’s entitlement to copyright protection to be an open question.

With that said, it would be quite a stretch for court not to find that graffiti is a work of expression fixed in a tangible medium—all that is required for copyright protection. Functionally, graffiti is a painting, no less so than Leonardo’s Last Supper fresco.

Things are even more complicated than that because most graffiti is painted on someone else’s property. Apart from the remarkable 5Pointz case (more on that below), very few graffiti artists have the explicit or even tacit permission of the property owners where the works are painted. So these cases set up the very real possibility that a graffiti artist could win copyright damages over reproduction of a work of art of which he or she cannot prevent the destruction.

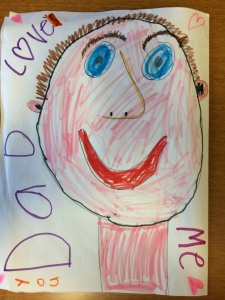

And yet, is that so strange? After all, the same is true of any visual work of art still protected by copyright. The following is a portrait of yours truly, composed by my daughter (remember, the camera adds 5 pounds):

I own the artwork, she owns the copyright. She can control its reproduction (reprinted below with permission, in loco parentis, of O’Donnell Minor Child). She can enjoin its copying, but I can physically alter or destroy the artwork (but I won’t!).

But even that is not so simple. As the 5Pointz case highlighted, but did not definitively answer, graffiti may still qualify for moral rights protection under the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990, 17 U.S.C. § 106A (VARA). The plaintiff artists in that case failed to obtain a preliminary injunction because the court was not convinced that the works were of “recognized stature,” one of the law’s elements. Yet it is not hard to imagine a better-known graffitist, (e.g., Banksy) from satisfying that element easily.

That, in turn, would set up the showdown that 5Pointz teased us with: the owner of private property constrained from its destruction or alteration because of the application of a painting to which he did not agree. Now that would be interesting.

None of this, of course, protects the artists themselves from the interim consequences of what the law otherwise regards as vandalism. Then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg (in a somewhat tone deaf manner, to most observers), wouldn’t absolve Banksy from vandalism charges, and instead characterized the work as evidence of “decay.” This is hardly a unique opinion, many recall with little glee a more-graffiti-filled past in New York, as an exhibition earlier this year at the Museum of the City of New York explored (“City as Canvas”). Likewise, the two German artists who planted a white American flag under cover of darkness atop the Brooklyn Bridge, whatever the expressive merit of that act, are essentially banned from returned to the United States unless they want to be arrested. Further, the flag that they left behind was a deliberate play on the actual U.S. flag (including stars and stripes), but in a uniform white color. What if that starts appearing in derivative works?

Lastly, don’t forget your Latin grammar if you get out your paintbrush: Romani ite Domum. Happy tagging, everyone.