There has been some renewed interest in the case a decade or so ago involving a claim by the heir of Oskar Reichel’s family to a painting in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston: Two Nudes (Lovers) by Oskar Kokoschka. In response I’ve decided to post an excerpt from my book A Tragic Fate—Law and Ethics in the Battle Over Nazi-Looted Art (ABA, 2017).

It has been suggested that the MFA somehow concealed its rationale or the documentary evidence on the basis of which it concluded that the painting should not be restituted. That is simply not so, however. The MFA’s now-curator of provenance, Dr. Victoria S. Reed, authored and the MFA filed an exhaustive report of the museum’s research into the case, accompanied by primary source documents. Whether one agrees or disagrees with its conclusions, the report has been publicly available for more than eleven years. It’s no secret that I have been complimentary of the MFA’s provenance research and transparency in the case—and I don’t think anyone would accuse me of being unsympathetic to claimants generally.

The key reasons for the MFA’s conclusions that the painting had not been sold under duress included the fact that Oskar Reichel’s sons pursued restitution claims vigorously (and successfully) for both real and personal property, including paintings. They never identified this painting in their claims to looted property, however. In addition, the MFA found—and filed publicly—correspondence from Oskar’s last surviving son Raimund from 1982 that explained that the MFA painting was among those that Oskar had given to Otto Kallir to sell in the USA:

Exhibit 65 to Dr. Reed’s Report

The MFA drew the conclusion, to which there was no specific evidence to the contrary, that this was in contrast to the property that had been taken from Oskar. This is in the context of the general presumption of invalidity for transactions between 1933 and 1945 involving persecuted groups.

I have been very critical of museums that I believe have not adhered to the spirit of the Association of Art Museum Directors’ guidance on Nazi-looted art claims where I think it is appropriate. But in my opinion—and that’s all it is, my opinion—the MFA is an example of a museum worthy of praise for following those principles of research and transparency (and not only with regard to Nazi-spoliation, but its collection generally).

Please do note that some of the analysis of the applicable statute of limitations has been superseded by the 2016 Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act (HEAR Act), but the case went to a final judgment before that law was passed and was thus not affected by it.

I urge you to consider the case with an open mind and reach your own conclusions. I have done my best to explain my thinking, which you may judge for yourself. The press coverage at the time was very critical (some of which resonated for me until I reviewed the case in detail), which in hindsight is probably attributable in part to the fact that I don’t recall any contemporary coverage that addressed specifically the actual research that the MFA did and made public.

The following is re-published with the permission of the author, and may not be copied, reproduced, or republished in any fashion without express written permission of the author, whom you may contact using the links on this page. A Tragic Fate—Law and Ethics in the Battle Over Nazi-Looted Art © Nicholas M. O'Donnell (2017) is available in hardcover and Kindle editions on Amazon.com. I hope you find it informative and thought provoking.

* * *

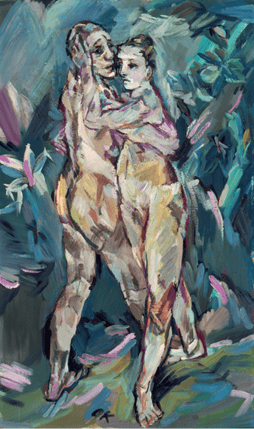

Oskar Kokoschka, Two Nudes (Lovers)

Oil on canvas

163.2 x 97.5 cm (64 1/4 x 38 3/8 in.)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Bequest of Sarah Reed Platt, 1973.196

* * *

The Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Oskar Reichel, and Provenance Research

Oskar Reichel was a Jewish doctor and art collector in Vienna. Before the Anschluss, Reichel and his wife Malvine lived with their son Raimund at Chimanistrasse 11 in Vienna’s leafy 19th District. They also had two other sons, Hans and Max. At some point, the Reichels opened an art gallery at Seilergasse 1 in the city center, right off the famous Graben street at the heart of the old city. Vienna had a large and integrated Jewish community, Reichel among them. In 1914, he acquired a 1913 painting by Oskar Kokoschka known by various titles, including Two Nudes (Lovers), Skizze (Doppelakt) (Sketch, Two Nudes); Liebspaar (Two Lovers); and Tanzpaar (Dancing Couple).

By 1917, Reichel had amassed within his collection at least eight paintings by Kokoschka. Over the succeeding years, he sold some of them but retained the 1913 painting. In May 1924, Reichel lent the painting to a man named Otto Nierenstein, owner of the Neue Galerie. That month, Reichel and Nierenstein corresponded about whether the painting might be for sale. Reichel indicated that it might be. The topic recurred many times over the next several years.

In or around 1933, Nierenstein changed his surname to Kallir. In June of that year, Reichel again lent him the 1913 painting. In 1937, Reichel was approached about loaning his Kokoschka paintings to the Museum für Kunst und Industrie (Museum of Art and Industry), known today as the Museum für Angewandte Kunst (Museum of Applied Art, or MAK). On April 22, 1937, Siegfried Troll of the museum wrote to Reichel at his home to confirm receipt of five works. Later correspondence confirms the receipt and insurance of the 1913 painting. The exhibition proceeded in May and June, and the painting is identified in the catalogue with Reichel as the owner and lender.

The annexation of Austria by Germany, or Anschluss, in March 1938 was an immediate catastrophe for Vienna’s Jews. With shocking swiftness, mobs began turning Jews out of their homes. The Ringstrasse, redeveloped around the old medieval wall of the city under Emperor Franz Joseph in the nineteenth century, is bounded both by monumental civic buildings, as well as palaces that were both residences and social centers. These buildings, like the Altmann residence on Elisabethstrasse, still define the visual character of the grand boulevard with which Vienna is now identified. As it happened, a large number of the beautiful homes were owned by Vienna’s Jews, who were targeted immediately.

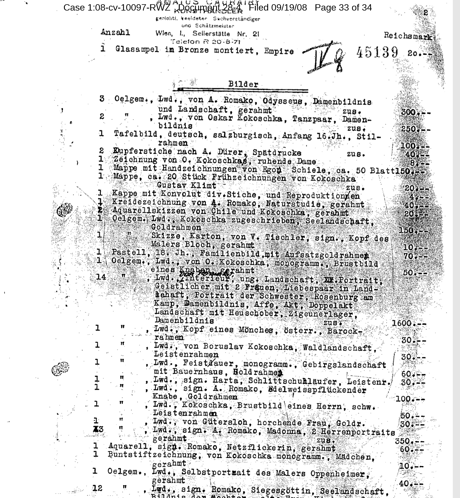

On the second to last page of Reichel’s mandatory property inventory (Verzeichnis), with several other items, notation appears in one place Tanzpaar (Dancing Couple) and in another Liebespaar in Landschaft (Lovers in a Landscape), an oil painting on canvas by “O. Kokoschka.” The list of paintings, attested by art dealer Amatus Caurairy, is dated June 25, 1938:

These inventories, as Jonathan Petropoulos has written, were hardly incidental or perfunctory. Instead, they were literally a road map for enterprising Nazis and looters:

[T]he Nazi Authorities instituted the Property Declaration requirement to monitor and control the property of Jews in Germany and Austria, with the ultimate goal of curtailing their economic influence. Property Declarations in fact were a prelude to the formal Nazi confiscation and seizure of all Jewish-owned property in Austria and Germany. Nazi legal decrees required Jews to report any sales of property items identified on the Property Declaration to an official Nazi authority and later to deposit the proceeds of such sales in to blocked accounts denominated in the name of the Jewish payee.

The compulsion to file these property declarations was accompanied by the creation of a centralized bureaucracy to enforce them. The Vermögensverkehrsstelle (property registration office) was empowered to seize and document Jewish property.

Jews in Austria suffered on Kristallnacht just as those in Germany did. In addition to the brutal violence across the newly enlarged Germany, a series of dispossessing decrees followed. On November 12, 1938, the Verordnung zur Ausschaltung der Juden aus dem deutschen Wirtschaftsleben (Order Regarding the Elimination of Jews from the German Economy) was enacted. This decree explicitly did just that by forbidding any trade or commercial activity by Jews. The Reich Economic Ministry soon adopted the tone described by Professor Petropoulos’s summary of the immediate availability of Jewish property but for limited exceptions (including, for the moment, a non-Jewish spouse).

Sometime on or after February 1, 1939, Reichel transferred five paintings to the Galerie St. Etienne in New York, Kallir’s new enterprise in the United States. On that date (February 1), Kallir wrote from New York to Reichel in Vienna to confirm the authorization for a shipping company to retrieve the works. An inventory reflecting the acquisition remains in the possession of the Galerie St. Etienne.

Kallir exhibited the 1913 Kokoschka in the United States over the course of the next several years. After the war, the painting was exhibited as part of a show entitled “Forbidden Art in the Third Reich: Paintings by German Artists Whose Work Was Banned from Museums and Forbidden to Exhibit,” sponsored by the Nierendorf Gallery in New York and shown there as well as the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston and the Worcester Art Museum. According to papers later filed by the Museum of Fine Arts, the painting was by then owned by the Nierendorf Gallery, but curiously, those papers do not explain how or when the ownership was conveyed from Kallir and St. Etienne. Nierendorf records indicate that the painting was sold from the show to E. Silbermann of the Silbermann Galleries in New York.

The painting was loaned to, among other places, the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Kallir wrote to James Plaut at MoMA on April 12, 1948,55 and references the paintings as in private hands at that point, with a reference to “Mrs. John Blodgett, of Grand Rapids, Michigan.” Over the intervening decades, the painting was loaned to a number of exhibitions, attributed to the ownership of Sarah Reed Blodgett, of Portland, Oregon. That same Sarah Reed Blodgett (Pratt) bequeathed the painting to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1973, where it has been ever since. Since then, it has appeared in catalogues raisonnée and exhibition catalogues identifying the MFA as its owner.

Reichel’s fate was far less salutary. Malvine Reichel, the titleholder to their Döbling home, sold it in 1939 to a couple she knew, Alfred and Herta Karrer. The Karrers’ ethnicity is unknown, but presumably, they were not Jewish. Malvine, who miraculously survived the war, later relinquished any claim to the home. By contrast, the Reichels sought restitution concerning their share in a building owned by Oskar at Börsegasse 12, which was adjudicated by the Restitution Commission in Vienna in 1953. Raimund, now living in Argentina, submitted two applications to the Fund for Assistance to Political Persecutees. This petition concerned both the livelihood that he and Hans had lost as Jews, as well as “[a] large art collection [owned by my father that] was forcibly sold: 47 pictures by the painter Anton Romako, which are today to be found in Austrian museums and private collections.” In 1953, however, the Verzeichnis were deemed classified by the Austrian government and unavailable to the public. Hans’s application was formally denied over a notarization issue that could not be resolved.

According to Reichel’s heir Claudia Seger-Thomschitz in her Counterclaim:

By the time Reichel died in Vienna in 1943, the Nazis had seized all of his material possessions, and had either murdered, incarcerated, or forced other Reichel family members to emigrate. The National Socialists murdered son Max in 1940, the year after the transfer of the painting to Kallir. Dr. Reichel’s wife, Malvine, was deported on January 15, 1943 to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Prague, where she remained until the end of the war. She lived the rest of her life in Illinois.

Hans and Raimund were thus Oskar’s sole surviving descendants. When Hans died, he left Raimund as his residual heir, and when Raimund passed away, he designated Claudia Seger-Thomschitz of Vienna (where he had returned) as his universal successor and heir.

According to Seger-Thomschitz, she first learned of the confiscated artworks when contacted by a Viennese museum in 2003 about the museum’s intention to return four Romako works to her as Dr. Reichel’s heir. After first retaining Austrian counsel to investigate, Seger-Thomschitz retained an American lawyer, who made a written demand on the MFA for the 1913 painting’s return on March 12, 2007. After some discussion, the MFA and Seger-Thomschitz agreed to a tolling agreement while the museum investigated further.

A tolling agreement is simply another way of describing an agreement to freeze the status quo with respect to the statute of limitations. Put another way, if a claim is timely, a tolling agreement allows the plaintiff to hold off on filing a case after what would otherwise be the deadline so long as the agreement is still in effect. Thus, if a claim subject to a three-year state of limitations is addressed in a tolling agreement the day before the deadline, the claimant could file the claim a day or a month after what would ordinarily be the deadline unless the tolling agreement has been terminated. By contrast, a tolling agreement does not provide a claimant with any rights she does not already have. So (as eventually happened), if Seger-Thomschitz’s claims were eventually deemed to have expired before March 2007, the tolling agreement could not revive them unless the agreement waives the limitations period regarding that party rather than suspending it (which it likely would not). Tolling agreements often make good practical sense for everyone, especially a defendant who is certain that he or she is right. Such agreements provide breathing space for a discussion and explanation, if there is one to be made, and avoid immediately entering the contentiousness and expense of full-blown litigation.

The MFA’s response has become a kind of Rorschach test for perspective about looted art restitution. Certain components are undisputed. The MFA engaged Victoria Reed, an art historian on its staff, to research the claim. Dr. Reed described her investigation in a lengthy affidavit that was eventually filed in court. Interestingly, there was not a sharp dispute between Seger-Thomschitz and the MFA (resulting from Dr. Reed’s investigation) about the provenance of the painting. Indeed, much of Dr. Reed’s exhaustive affidavit is addressed to the history and public availability of its whereabouts after the war.

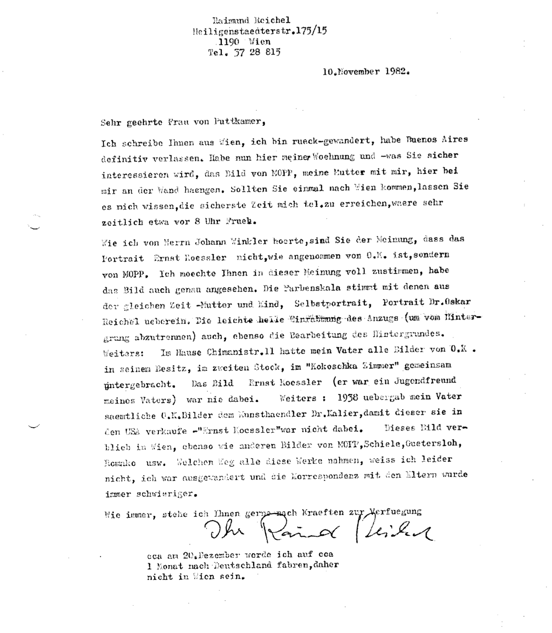

After reviewing the history, the MFA came to a few salient conclusions. First, it maintained that the 1939 sale was entirely voluntary and not the subject of compulsion. The MFA made much of Reichel’s relationship with Kallir and the failure to include the 1913 painting explicitly in any of the various efforts at restitution after the war. Reed’s affidavit, interestingly, includes what might be regarded as the thesis statement of the MFA’s position only at the very end. It cites a November 10, 1982, letter from Raimund Reichel Marie-Agnes von Puttkamer, a Viennese art historian. Raimund’s letter states (in the MFA’s translation):

In the house on Chimanistrasse 11, my father put all the paintings he had by O.K. in the ‘Kokoschka room’ on the second floor. . . . Further: [I]n 1938 my father transferred the entire collection of O.K. paintings to the art dealer Dr. Kalier [sic], so that he could sell them in the U.S.A.

The clear implication of this, the MFA argued, was that Dr. Reichel had involved Kallir voluntarily for the purpose of selling the paintings for Reichel’s benefit and without any duress.

Seger-Thomschitz took an entirely different tack from a factual perspective. She noted the secrecy of the Verzeichnis until at least 1993, arguing that the very contents of Reichel’s declaration were unknowable between the Anschluss and decades later (and critically, after the 1982 letter). There is another aspect of the 1982 letter that was never adjudicated because of the approach that the court eventually took, as will be seen. Review again the MFA’s translation of the letter. The original document is attached to

Dr. Reed’s affidavit, and not surprisingly, it is in German. The ostensible purpose of the letter is to discuss not the 1913 painting at issue, but rather a portrait of Ernst Koessler and whether it was by Kokoschka or Max Oppenheimer, referred to as “MOPP.” It reads with regard to the Kallir transaction (author’s translation):

Further: [I]n 1938 my father gave collected OK pictures to the art dealer Kallier [sic], with which to sell them in the USA. “Ernst Koessler” was not among them. This picture remained in Vienna, as with other pictures by MOPP, Schiele, Gütersloh, Romako, and so on. Which route these pictures took, unfortunately I do not know.

This is a critical document. Raimund’s statement certainly implies familiarity with the contents of his parents’ house, as well as at the very least the fact of the transfer to Kallir. In addition, he makes a point of saying when he does not know the fate of the paintings under discussion. One reading of that statement is to conclude that Raimund did have information about the others. If he did, it would undercut Seger-Thomschitz’s position that he (and then she) could not have known about the Kokoschka paintings until the contents of the property declarations were brought to their attention.

On the other hand, the statement about Kallir and the United States has its own ambiguity. If Reichel gave the paintings to Kallir to sell them in the United States, is the likeliest meaning that Reichel sold the paintings to Kallir and that the eventual decision to sell them in the United States was Kallir’s decision alone after taking title to them, or that Reichel entrusted the works to Kallir for eventual sale in the United States, or that Reichel consigned the works to Kallir? If it were the first scenario, then certainly no successive holders would have a title problem; they would be Reichel’s proper successors just as much as Kallir’s. If it were the last scenario (consignment), it might not make a notable difference either. A consignee has legal authority to sell a consigned object, and a subsequent good-faith purchaser for value from a seller in the ordinary course could claim title. They would, in that case, not be taking title from a thief. The consignor—who gave the property to someone with the legal power to sell it—has a remedy against the consignee (Kallir), not the subsequent owner. But, what of the middle scenario? It would certainly be fact-intensive—if there were more facts. In any event, none of this can be examined further, because Raimund died and cannot be asked what he meant.

The MFA satisfied itself that the painting was not stolen from Reichel. Seger-Thomschitz disagreed and did not waiver in her claim for it, however. At this point, the MFA took a controversial step and sued Seger-Thomschitz to “quiet title.” This procedural maneuver, which is not unusual as a general matter, asks a court to answer the same question but posed by a different actor (and is a routine event in real estate title questions in particular). Rather than the person without the property asking the court to compel the possessor to give it back, a quiet title declaratory judgment action seeks a statement from the court that the current possessor is, in fact, the owner, superior to any other claimants. Although not odd procedurally, the optics were jarring to many, whereas others praised the MFA’s thoroughness. According to the Boston Globe:

Ori Soltes, cofounder of the Holocaust Art Restitution Project in Washington, D.C., said he was impressed by the museum’s research. “It strikes me the MFA’s case has a lot of merit,” Soltes said.

“MFA sues to bolster claim to disputed 1913 painting,” Boston Globe, January 24, 2008. On the other side, Rabbi Howard Berman wrote to the Globe and said:

THERE MAY well be legal merit to both sides of the argument regarding the ownership of the disputed Kokoschka painting by the Museum of Fine Arts (“MFA sues to bolster claim to disputed 1913 painting,” City & Region, Jan. 24). However, it is appalling that deputy director Katherine Getchell would equate the horrors already facing the Jews of Austria by 1939 with the “duress” of financial pressures during the Depression, or the current mortgage problems in America.

The violent persecution of the Jews of Germany and Austria was well underway by the time the Reichel family sold the painting. There can be no question that the elderly couple faced enormous fear and desperation as their sons fled the country and one was interred in a concentration camp. Getchell’s insensitivity to these realities is very disturbing, and diminishes the MFA’s moral stature in this complex controversy.

“Rabbi: MFA Director Insensitive,” Boston Globe, January 26, 2008.

Regardless of the public reaction, the battle was underway. Seger-Thomschitz answered the Complaint and filed a Counterclaim of her own for return of the painting. She articulated the foregoing history, and argued that any uncertainty should be resolved against the MFA and not her. Notably, she cited the presumption that any transfer in Nazi Germany (as Austria, literally speaking, was in 1939) involving a Jew is presumptively invalid. This unassailable notion has many roots in both common sense and legal action by the Allies. In particular, Seger-Thomschitz articulated the importance of MGL No. 59, whose stated purpose was “to effect to the largest extent possible the speedy restitution of identifiable

property . . . to persons who were wrongfully deprived of such property within the time period from January 30, 1933 to May 8, 1945 for reasons of race, religion, nationality, ideology or political opposition to National Socialism.” 12 Fed. Reg. 7983§ 3.75(a)(1). As discussed, the touchstone of this presumption is that it could be rebutted only where it could be shown that the seller was paid a fair price and had free disposal of the proceeds. Making explicit common-law concepts of the priority of the true owner over subsequent holders, even those innocent and in good faith, it states that “property shall be restored to its former owner or to his successor in interest . . . even though the interests of persons who had no knowledge of the wrongful taking must be subordinated. Provisions of law for the protection of purchasers in good faith, which would defeat restitution, shall be disregarded except where Law No. 59 provides otherwise.” See MGL No. 59. (Emphasis added.)

The MFA moved for summary judgment. Summary judgment, distilled to its essence, asks the court to conclude that no factual resolution is necessary. If all the facts that are material to the causes of action are undisputed, then the legal consequence of those facts can, and indeed should, be determined by a judge, not a jury. By contrast, if something essential to the claim is in dispute, then a trial is necessary for either a jury, or a judge as fact finder, to resolve conflicting versions of events, credibility, and similar competing facts.

The legal thrust of the motion was purely procedural. Whatever the circumstances in 1938, the MFA argued, Seger-Thomschitz’s claim was too late to bring in a Massachusetts court. To advance this argument, the MFA first had to convince the court to apply a particular law. Federal courts have various avenues to assert jurisdiction, as we have seen. Among them is so-called diversity jurisdiction, which refers to conflicts between parties from different locations under the right circumstances. Thus, the MFA’s case was brought in diversity pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1332 as a dispute in excess of $75,000 between citizens of different states (in this case, Massachusetts and Austria). In such a case in federal court, however, there is no federal cause of action or federal law to apply. The question then becomes which law to apply. A federal court in diversity looks first to the choice of law rules of the forum (which is distinct from, and does not presuppose the eventual application of, the substantive law of the forum). Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Elec. Mfg. Co., 313 U.S. 487 (1941).

The MFA argued that Massachusetts law should apply to the dispute over a painting in Massachusetts against a Massachusetts nonprofit entity. Like many states, Massachusetts looks to the Restatement (Second) of the Conflict of Laws, § 142. In that view, the forum court will apply its own substantive statute of limitations if it bars the claim. New England Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Goudreau Constr. Co., 647 N.E.2d 42,45-46 (Mass. 1995). If it does not bar the claim, then the forum state will apply its law to permit the claim unless the defendant establishes that the claim serves no substantial interest in the forum and the claim would be barred by a state with a more significant interest. Fedder v. McClennen, 959 F. Supp. 28, 35 (D. Mass. 1996).

With that in mind, the MFA argued that the various tort claims brought by Seger-Thomschitz (replevin, conversion) were barred by Massachusetts’s three-year statute of limitations. Generally, that limitation period will run from the time of the injury. That would have ended the timeliness of any claim in 1942.

Massachusetts, like most states (critically excluding New York’s demand and refusal rule as described further herein) also use the discovery rule for torts, however. That is to say:

The limitations period begins to run ‘when a plaintiff discovers, or at an earlier date when she should reasonably have discovered, that she has been harmed or may have been harmed by the defendant’s conduct.’ . . . The limitations period is tolled until ‘events occur or facts surface which would cause a reasonably prudent person to become aware that she or he has been harmed. A person is considered to be on ‘inquiry notice’ when the event first occurs that would prompt a reasonable person to inquiry into a possible injury.

Epstein v. C.R. Bard, Inc., 460 F.3d 183, 187 (1st Cir. 2006). This is the fundamental basis of the Museum of Fine Art’s motion. It avoids arguing or undertaking to prove whether the 1939 sale was, in fact, legitimate. Instead, it argues that the circumstances of the transaction, and the subsequent history and location of the painting, were sufficiently knowable that a reasonably prudent person would have discovered it at some point in the time between the transfer by Kallir in Vienna and more than three years before the case was filed.

Although the MFA’s motion was not directed toward proving that Reichel freely sold the painting, those same facts were squarely targeted to arguing that the Reichels—Oskar and then Raimund—knew who had sold the painting thereafter (Kallir) and that the painting’s whereabouts were reasonably ascertainable in the intervening period. Indeed, Raimund’s correspondence as referenced in Dr. Reed’s report is referenced heavily for just that purpose. Not only, argued the motion, did the 1982 letter refer to the rooms filled with Kokoschka paintings that were sold in the United States (with no apparent complaint), but the motion identifies another letter from 198564 in which the specific painting is mentioned. By the terms of that letter, Raimund later spoke with Kallir in New York, who

claimed to have “lost his shirt.” Lastly, although the MFA contested the idea that the 1939 conveyance was under duress, it suggested that the belief would have compelled only a reasonable owner to inquire immediately, if he thought he had been robbed.

Lastly, even accepting for the sake of argument that Raimund might never have had sufficient facts to discover the basis for his claim, the MFA noted that more than three years had elapsed since Seger-Thomschitz’s U.S. counsel had made a demand for the return of the painting. The point is that even if the statute of limitations were tolled, ignored, or otherwise set aside from the 1939 conveyance to the modern era, Seger-Thomschitz knew enough by no later than 2003 that she had an argument as to the painting’s ownership.

Seger-Thomschitz countered with a different theory. Although the MFA’s claim was brought in diversity, Seger-Thomschitz argued that her claims actually implicate federal, not state law. In that event, there would be no choice of law analysis; rather, federal law would apply. Seger-Thomschitz went on to articulate that her claims were supported by the allegation that MFA’s acquisition and retention of the paintings were in violation of its implicit promises under the Internal Revenue Code, specifically § 501(c)(3) that confers charitable status. These breaches of the museum’s obligations, in Seger-Thomschitz’s characterization, were the basis for the claims and therefore the source of applicable law. With this in mind, she took the offensive and accused U.S. museums more broadly of failing to take claims for restitution seriously and thereby breaching their implicit promises to the public as nonprofits. In this vein, she argued, the court should not apply strictly the three-year statute of limitations. Rather, she suggested, the court should apply a flexible standard by invoking principles of equity (and thus ruling out the application of a laches defense, which is an equitable defense).

As to the application of the three-year statute of limitations, however, Seger-Thomschitz faced her greatest, and ultimately fatal, hurdle. She argued in her opposition that she could not have known, and did not know, of the existence of her claims, until 2003, and promptly retained counsel to investigate. But, she did not articulate any explanation for the correspondence involving Raimund, her predecessor, in the years before 2003. Nor did she provide context for the timing of her discovery of her claim relative to the filing of a claim (or counterclaim). She did not make a formal demand or reach the tolling agreement with the MFA until 2007, by any measure more than three years after the discovery in her version of events in 2003.

Ultimately, the court sided with the MFA. The court issued a Memorandum of Decision and Order on the MFA’s motion on May 28, 2009. It did not reach a conclusion on whether the 1939 sale was legitimate, rather, it decided the motion entirely on statute of limitations grounds. See Museum of Fine Arts v. Seger-Thomschitz, Civil Action No. 08-10097-rwz, 209 U.S. Dist. LEXIS at 26–27 (D. Mass May 28, 2009). It did, however, incorporate into the decision reference to the 1982 and 1985 correspondence from Raimund about his father’s Kokoschka paintings. First, the court rejected Seger-Thomschitz’s request to ignore the Massachusetts statute of limitations and apply some federal common law standard because the court disagreed that the 1939 transaction was so obviously coercive. Although perhaps a slight distinction, this conclusion, while not ultimately a ruling on the title transfer itself, is clearly informed by the MFA’s explanation of the history and claim to legitimacy. However, unconvinced of a compelling reason to set aside the statute of limitations, the court declined to do so.

Similarly, the court did not accept Seger-Thomschitz’s creative theory that her claims were contract-based rather than torts. Seger-Thomschitz pleaded no agreement between her and the MFA that was allegedly breached, rather she alleged the MFA’s wrongful possession. Instead, the court concluded, “[s]uch claims clearly sound in tort, not contract, and thus is subject to the three-year limitations period.” Id. at *21. Under that limitation, the court concluded that the claim was time-barred even under the discovery rule. First, it held, the Reichel family “had sufficient knowledge of Reichel’s ownership and transfer of the painting to put them on notice of a possible injury.” Id. at *23. The court was also swayed by the request by Reichel’s son for restitution for some property but not the painting at the center of the lawsuit. That conclusion would be dubious on a summary judgment posture if standing alone. It does not necessarily follow that because the family knew of specific, personal property later identified for restitution that the family also knew of other specific, personal property, which could easily have been obscured or unknown.

Raimund Reichel was subjectively aware of the Kokoschka paintings and discussed them specifically decades after the war. Combined with the frequent exhibition of the paintings over the years, the court held Raimund—and thus Seger-Thomschitz as his successor—to that duty of inquiry, and that if he or they believed they were aggrieved they could have known sooner than 2003 had they exercised the diligence required by the court. The court made a point to underscore the justification for limitations periods, citing the diminishing availability of evidence. Id. at *28, citing Am. Pipe & Constr. Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538, 554 (10742). Indeed, the court took the occasion to contrast the Reichel family’s approach to the one used by Max Stern’s Estate.

Lastly, even if any of the foregoing were sufficiently disputed as a matter of fact to warrant summary judgment (which, to be clear, the court did not accept), the court held that the claim was still too late because Seger-Thomschitz waited more than three years to make a demand and/or secure a tolling agreement. By the time the MFA filed suit, let alone by the time she counterclaimed, Seger-Thomschitz could not claim to have discovered the basis for her claim within three years. Summing up, the court stated:

The conclusion is inescapable that, in 2003, [Seger-Thomschitz] knew or should have known of Reichel’s previous ownership of the Painting, his transfer of the Painting to Kallir and the MFA’s current ownership, all of which was public knowledge and easily discoverable. Because she did not make a demand on the MFA until 2007, Seger-Thomschitz’s claims are time-barred, even if the cause of action were tolled until 2003.

Id. at 830. The court was no more persuaded by Seger-Thomschitz’s allegations concerning Kallir and fraudulent concealment that would toll the statute of limitations because, it noted, any alleged misdeeds by Kallir preceded the MFA’s predecessor in title and Seger-Thomschitz’s knowledge no later than 2003.

The court repeatedly referenced and contrasted the Vineberg decision, comparing the Stern estate’s efforts over the years to find the subject of that litigation from the Reichel’s silence over the years about the Kokoschka painting at the MFA. Although the question of title or the validity of the 1939 transaction were never explicitly reached because of the timeliness question, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the court agreed with the MFA in the view that the painting had not actually been stolen from Reichel or taken under duress.

Seger-Thomschitz appealed the dismissal, but the First Circuit saw no reason to disturb the District Court’s ruling. Museum of Fine Arts v. Seger-Thomschitz, (23 F.3d) (1st Cir. 2010). The First Circuit was more circumspect about how to view the 1939 transaction, summing it up by saying “details of this transaction are sketchy.” Id. at 4. Noting that the only question before it was the question of timeliness, the First Circuit expressly observed that the question of the validity of the 1939 conveyance is not “clear cut.” Id. at 6. Seger-Thomschitz apparently abandoned the contract theory of statute of limitations on appeal and pressed the applicability of the discovery rule to argue that she was within the applicable period. The First Circuit removed any doubt as to what the outcome would be with this passage:

The party seeking the benefit of the discovery rule has the burden of showing (1) that she lacked actual knowledge of the basis for her claim and (2) that her lack of knowledge was objectively reasonable. Koe v. Mercer, 876 N.E.2d 831, 836 (Mass. 2007). Courts applying the discovery rule in missing art cases have tested the reasonableness of the claimant’s lack of knowledge by asking whether the claimant “acted with due diligence in pursuing his or her personal property.” O’Keeffe v. Snyder, 416 A.2d 862, 872 (N.J. 1980); accord Autocephalous Greek-Orthodox Church v. Goldberg & Feldman Fine Arts, Inc., 917 F.2d 278, 288–89 (7th Cir. 1990); Erisoty v. Rizik, No. 93-6215, 1995 WL 91406, at *10 (E.D. Pa.

Feb. 23, 1995).

In contrast to many missing art cases, the location of the Painting has been no secret in this case. The Painting has long been on public display at the MFA, a major international museum. Since 2000, the MFA has listed the Painting in a provenance database on its publicly accessible website. Several published books and at least one catalogue raisonné of Kokoschka’s works identify the MFA as the current holder of the Painting.

Id. at 7.

Under this standard, the First Circuit also found the correspondence from 1980s to be dispositive of the question of whether a dispossessed claimant could have known sooner of the claim. That is to say, assuming for the sake of argument that the paintings were stolen, the letters showed Raimund’s subjective awareness of their existence and location in the United States. Given that, a properly motivated claimant would have investigated further, and, more important, could have located the painting at the MFA with a reasonably diligent search. The discovery rule does not require the possessor to prove any more.

In any event, as noted by the District Court, even under Seger-Thomschitz’s version of events, she knew of the painting’s location no later than 2003, making the application of the discovery rule more or less irrelevant. Again, assuming for the sake of argument that the painting had been stolen and neither Raimund nor Seger-Thomschitz could possibly have known where it was, Seger-Thomschitz did know in 2003, more than three years before the MFA’s lawsuit and therefore, by definition, more than three years before Seger-Thomschitz’s Counterclaim.

At the time, the MFA’s strategic decision to dismiss the case on statute of limitations grounds provoked some controversy. Notwithstanding the District Court’s pronouncements regarding the purpose of limitations periods, the assertion of a timeliness defense is seen as inconsistent with the prevailing view espoused since the Washington Principles, i.e., reaching what could be deemed fair and just solutions with respect to claims for stolen art. From that perspective, the MFA’s litigation tactics prevented the fundamental question about whether the 1939 conveyance was valid. Although the District Court’s opinion was perhaps more open regarding its view of the transaction, not surprisingly the First Circuit was more cautious when stating that that particular question was not before it, and thus no inferences about it should be drawn from the decision on timeliness.

From the other perspective, however, the MFA’s rationale was straightforward. It believed that the 1939 sale was not coerced and that all transfers thereafter were legitimate. Winning the case and quieting title to the paintings through the statute of limitations was therefore the quickest way to confirm what it had subjectively concluded: that the painting was not looted art. Additionally, there is no question that the MFA drew its conclusion from a substantial investment of time and resources. Were it not for the 1980s correspondence, the 1939 transaction would look very different, and the gaps in information would have to be held to support a finding of duress. The gap between the Anschluss, the forced property declarations just months later, and the complete chaos that befell Vienna’s Jews do not permit any other rational conclusion in the abstract. However, in this case, those letters address a subjective understanding of the fate of the paintings and do not address the concern that the conveyance

had been other than what Reichel wanted. The timeliness defense was the shortest route to that result. As later litigations will reveal, the assertion of nonsubstantive defenses is not always supported by this use of exhaustive effort and the presence of evidence to legitimize the transaction. The MFA’s belief that it was warranted in retaining the painting goes a long way to distinguishing it from other museums that seem indifferent to their collections’ looted past.