Since the passage in 2016 of the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery (HEAR) Act, many commenters (here included) have grappled with what the implications of the law will be on the scope and frequency of future claims. Even as litigants are faced with policy arguments about whether individual claims belong in U.S. courts—arguments that the HEAR Act should have put to rest—it is occasionally worthwhile to consider how prior cases would have been affected. Such analysis can draw into relief why the law was such a significant step forward. This week, news that a painting by Vincent Van Gogh once owned by Elizabeth Taylor will go to auction again provides one such example. A beautiful painting in the collection of the biggest movie star in the world makes for a great sales pitch, but missing in the coverage is any mention of Margarethe Mauthner, a German Jew who owned the painting before fleeing the Nazi regime. The exact circumstances under which she lost possession of the painting are unclear, but those circumstances might have had the chance to be determined had the HEAR Act been passed earlier. The importance of that opportunity is worth considering as the law is assessed going forward.

From the Christie's announcement:

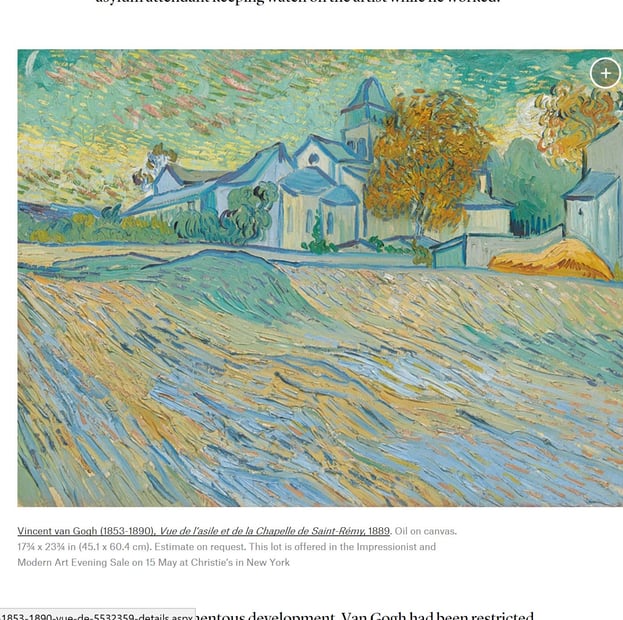

Margarethe Mauthner was a German Jew. Sometime before 1928, she acquired Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy, which Van Gogh painted in the last year of his life. It shows the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where he was being cared for. As for Mauthner, according to the 2004 lawsuit filed by her heir Andrew Orkin against Taylor, a 1928 catalogue raisonné (a book identifying an exhaustive list of a particular artist’s entire body of work), Mauthner had the painting by 1928, and a second catalogue raisonné in 1939 also listed Mauthner as the owner. Before Mauthner, the work had belonged to renowned art dealer Paul Cassirer, who acquired it in 1907. The parties to the lawsuit did not agree as to when Cassirer ceased having it. Taylor purchased the painting in 1963 at Sotheby’s.

Taylor’s fame needs no explanation, but who was Mauthner? As the U.S. District Court in Los Angeles explained and as I discussed in A Tragic Fate—Law and Ethics in the Battle Over Nazi-Looted Art (Ankerwycke 2017):

As the Nazis' persecution accelerated, Mauthner fled Germany to South Africa in 1939, leaving her possessions behind. She remained there until her death in 1947, at the age of 84. What happened to Vue de l'Asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Remy during that time is not clear from the record.

Mauthner’s heirs alleged that having fled under persecution, and in the absence of evidence to the contrary, the sale must be considered coercive and therefore invalid under the presumption of Military Government Law No. 59. The painting was acquired at an unknown date by Alfred Wolf, who was the consignor listed in the 1963 Sotheby’s catalogue.

Orkin sued Taylor asserting that has Mauthner’s heir, he was the true owner of the painting. His case was dismissed because the court held that California’s statute of limitations had expired. Orkin v. Taylor, 487 F.3d 734 (9th Cir. 2007). Orkin had also argued for the existence of a right to sue under the Holocaust Victims Redress Act of 1998, an argument which courts never adopted. As a result of the dismissal, the parties never litigated the factual question of the validity of the sale, and the court never had to decide against whom the historical uncertainty should be held—Mauthner’s heirs, or Taylor.

The District Court held that California’s statute of limitations had expired no later than 1993, three years after Taylor’s ownership was publicly knowable (in the Court’s view). Had the question come up today, the relevant inquiry would not have been whether three years had expired since then, but six because the HEAR Act supersedes all state statutes of limitations and defines the new period as six years. As such, the result may have been the same (assuming the same facts and filing date of the case).

But the inquiry itself could have been affected by the HEAR Act, which expresses a strong preference to give litigants their day in court without facing assertions that the claims are too late (and which would not have been bound by the California state precedent that determined the Orkin decision). For example, the court held that the presence of the painting in an exhibition catalogue in 1990 put Mauthner’s heirs on notice (the legal requirement for when a claimant could know to whom their claim applied). The District Court held that a reasonably diligent plaintiff would have found that exhibition catalogue.

That was a bit of a leap on a motion to dismiss, which is decided before any facts are actually resolved. Auction and exhibition catalogues were not universally available or accessible before the Internet. Suggesting that the existence of a catalogue, somewhere , instantly puts everyone in the world on notice as to its contents, is a stretch even in 2018. It certainly wasn’t the case in 1990.

The painting was sold in 2012, well after the lawsuit was decided. Now it heads to auction again, with an estimate of $35 million. Coverage of the listing rightly addresses the significance of the work in Van Gogh’s oeuvre, and Taylor’s prior ownership of the painting is understandably of interest to potential buyers. To be clear, Christie’s listing accurately describes the painting as with Mauthner after Cassirer and before Wolf, and Christie's restitution department deserves credit for the positive effect that it has had on market standards in the last twenty-five years.

That provenance, however—which very few people will read, certainly compared to the news coverage—is the only mention I have been able to find even of Mauthner’s name in the coverage of the sale.

Margarethe Mauthner is part of the history of the Van Gogh painting in a way that is just as important, and far more powerful, frankly, than Elizabeth Taylor. The HEAR Act does not revive claims already adjudicated, so the current owner can sell the painting without any concern about having valid title, but hopefully the HEAR act will allow stories like Margarethe Mauthner’s to be told more fully in the future.