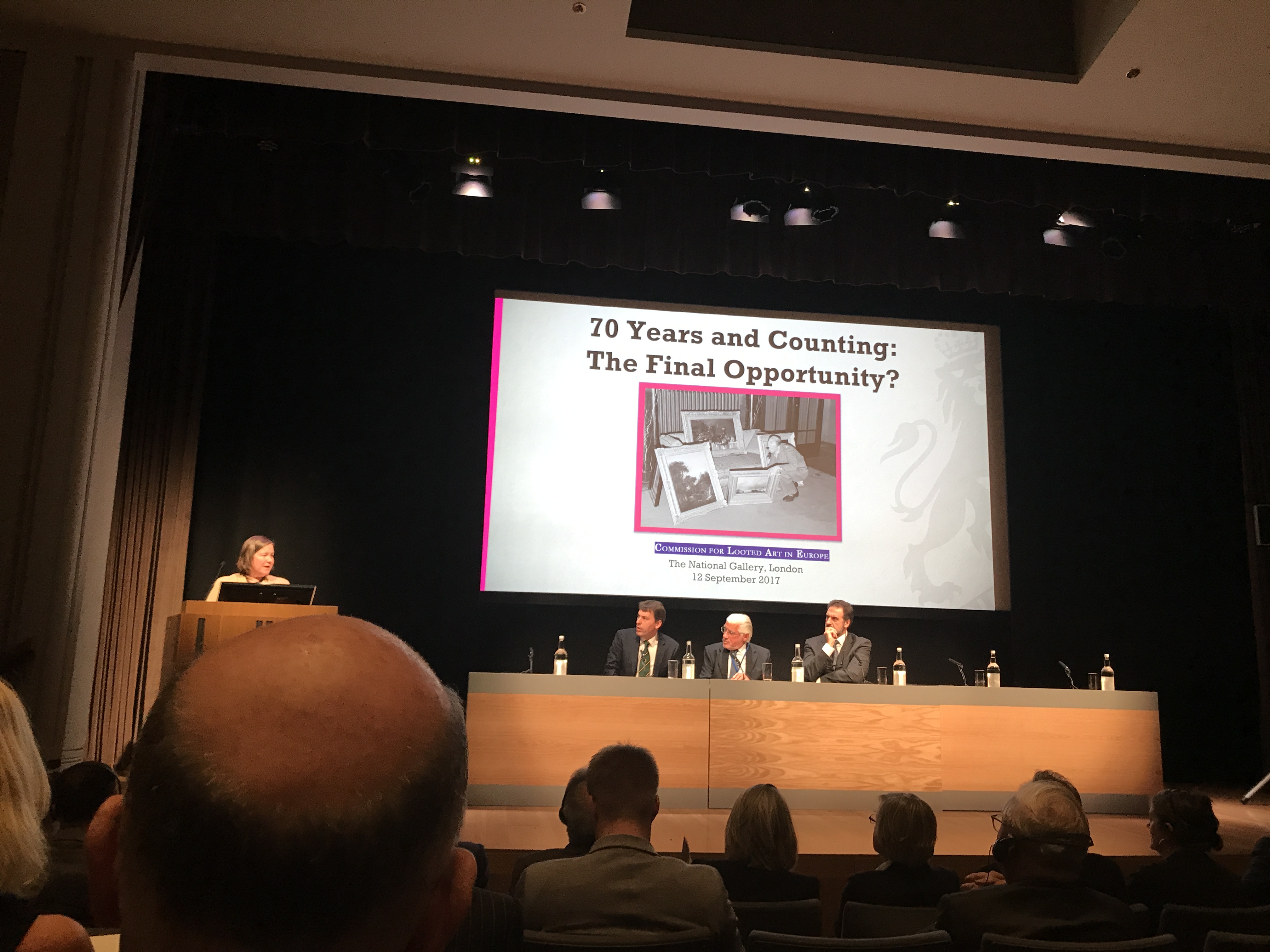

The National Gallery London hosted on September 12, 2017 the much-anticipated conference “70 Years and Counting: the Final Opportunity?” organized by the United Kingdom Department for Digital, Culture Media & Sport (DCCS), and the Commission for Looted Art in Europe (CLAE). Delegates from numerous countries gathered to consider the state of progress on the efforts to identify and return works of art lost during the Nazi era. While the event had a truly international flair, the discussion centered primarily on the five countries that have created some sort of process to consider assertions of looted art in response to the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art: England, France, Austria, the Netherlands, and Germany.

It was an impressively organized day, and an important presentation of the state of affairs. The overwhelming vibe among those in attendance was a quiet frustration, for sure. The tone of the conference was civil and professional, but that does tend to soften the opportunity to spotlight failures or missed opportunities. It was regrettable, I thought, that the only country that audience members felt comfortable criticizing forcefully was Poland. Poland certainly has some explaining to do, but it is hardly the only one. Germany’s Advisory Commission, for example pitched a number of rose-tinted claims about its work that are belied by the positions it has taken in court.

I don’t think anyone expected a dramatic sweeping consensus of a way forward to emerge. But as frustrating as the pace of progress can be, the world does not stand still. There are claimants who know the rules of the road from painful experience, but new claims come to light all the time and introduce those families to a baffling and daunting situation. Events such as this are of important value, and a number of claimants organized some organic discussions over the course of the day during breaks.

If I could change one thing, it would be to include the perspective of the United States. There was plenty to fill one day with the important questions facing institutions and objects in Europe, so perhaps the U.S. experience would have required additional time. But those same disputes have many connections to U.S. claimant families, and of course as the organizer of the Washington Conference, the way in which the issue has played out here is just as important (and just as worthy of scrutiny, to be clear). Love it or hate it, U.S. policy, disputes, and law are as influential as those in any other country involved (shameless plug here for A Tragic Fate, which analyzes just that).

The director of the National Gallery, Gabriele Finaldi, David Lewis of the CLAE, and John Glen, MP and Minister for the Arts, Heritage and Tourism, gave opening remarks stressing the need for transparency and urgency. MP Glen announced what had just been made known, namely, the existing sunset provision of the UK Spoliation Advisory Panel (SAP) had been removed, make the panel able to continue indefinitely. Lewis lamented that in so many cases, little progress had been made.

There were four principle sessions, and a concluding summation. The first panel was entitled “Lost Art: experience of claimants and institutions,” chaired by Sir Paul Jenkins, KCB, QC (and former head of the UK Legal Dispute Department). The presenters were curator Dr. Antonia Boström of the Victoria and Albert Museum, lawyer Imke Gielen of von Trott zu Solz Lammek in Berlin, Simon Goodman (author of the superlative The Orpheus Clock), and Anne Webber, co-chair of the CLAE.

Webber began by pointing out the flip side of the five panels present, namely, the absence of process in any of the other signatories of the Washington Principles. Even for those present, the lack of rules of process makes consistency and transparency hard to predict, and the onus remains on the claimant to know where things are and to take the initiative. Goodman commented on his personal experience in seeking the Guttmann collection before several of the commissions, noting that national collections afforded some opportunity but are difficult “even when you know what you’re doing.” Under the best of circumstances there are logistical obstacles like lack of photography and similar but different names for works of art. Gielen pointed out that the criteria and considerations are not consistent across the commissions, including in particular whether to take into account the moral position of the parties. She noted the irony that not all the rules imposed by the Allies on Germany apply to commissions in those victorious countries. She was less optimistic still about the many countries with no process, recounting stonewalling in Poland and Russia in particular. Dr. Boström remarked that for her it is a question of resources (though happily she announced that the V&A has appointed a full time curator of provenance).

The second panel was entitled “National claims processes” and featured a representative from each of the five commissions: moderator Sir. Donnell Deeny (chair of the United Kingdom Spoliation Advisory Panel), Professor Jan Bank of the Restitutions Committee of the Netherlands, Dr. Reinhard Binder-Krieglstein of the Art Restitution Advisory Board in Austria (Kunstrückgabebeirat), Professor Dr. Reinhard Rürup of the German Advisory Commission, and Jean-Pierre Bady of the Commission pour l’indemnisation des victimes de spoiliations (CVIS) in France. Each member summarized the history of their respective commission and the general terms of appointment. It was a concise point of departure for further discussion about each panel, but the discussion stayed pretty high level and did not delve very far into comparison or contrast, let alone any criticism. Nonetheless it was the kind of pithy summary of the various commissions that is often hard to find.

The third panel was named “Unlocking the archives: accessibility and disclosure.” It consisted of moderator Richard Aronowitz-Mercer (Head of Restitution, Sotheby’s Europe), Dr. Christian Fuhrmeister (Project Leader, Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Munich), Kristian Jensen (Head of Collections and Curations, British Library), Dr. Johannes Nathan (Nathan Fine Art in Potsdam and Zurich), and Margreet Soeting (Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam). As the titled indicated, the presentations covered the accessibility of archival materials, both public and private. Nathan commented on his own family’s experience as art dealers and claimants, and the role that businesses’ papers can play in learning more. Dr. Fuhrmeister discussed his frustration with the paltry funds doled out by the Lost Art Foundation and the lack of timeliness and transparency in those funding decisions to allow research to continue. Soeting recounted a fascinating tale of the records of the Stedelijk Museum nearly being lost to an administrative housekeeping, records that showed in many cases works that were deposited for safekeeping in advance of the German invasion. Interestingly, the discussion soon crossed from archives to the tension between the value of information and the interests of transparency. Not only that, but efforts to universalize databases have run aground on European data protection law in many instances. The novel idea of some private insurance market as a solution was bandied about as well.

The last full panel concerned private collections. Moderated by Pierre Valentine of Constantine Cannon LLP, it included Monica Dugot (Christie’s International Director of Restitution), Martin Levy (H. Blairman & Sons Ltd. and member of the UK SAP), Katrin Stoll (Neumeister Auction House in Munich), and Isabel von Klitzing (provenance researcher and art consulting). Stoll’s auction house engaged in a remarkable act of transparency when she discovered that her company had the archives of the Weinmüller Auction House in Vienna that had sold many expropriated collections. Stoll and her company swiftly assembled and published the records. Dugot recited some of Christie’s history in dealing with private claims, noting that they had helped with 230 resolutions, some 20% of which were for less than $10,000. She noted in particular that some sense of shared definitions would help, concerning forced sales, for example.

The day ended with Tony Baumgartner of Clyde & Co (and Deputy Chair of the SAP) giving an impressive in the moment synthesis of the ideas and discussion of the day.

There was general consensus that another five years should not go by before gathering again, and tentative discussions were had about a similar event, possibly in Vienna, in two years.