I recently tackled the public discussion in Germany about whether to rename the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, the foundation that oversees the State Museums of Berlin and some of the most remarkable collections in the world. Readers of the Art Law Report will know this name well, the SPK is the defendant in the lawsuit brought by my clients for the restitution of the Welfenschatz, or Guelphe Treasure, that the Supreme Court heard in 2020. While I've never been shy about criticizing the SPK about its approach in our our case (which is on appeal, briefs here and here), this piece addresses a different question. Namely, what place does the name "Prussia" have in the 21st century? For anyone like me who still thinks about the historical sliding doors of the Grossdeutschelösung and Kleindeutschelösungdebate of the 19th century about how to unite the German-speaking states and duchies, this piece is for you.

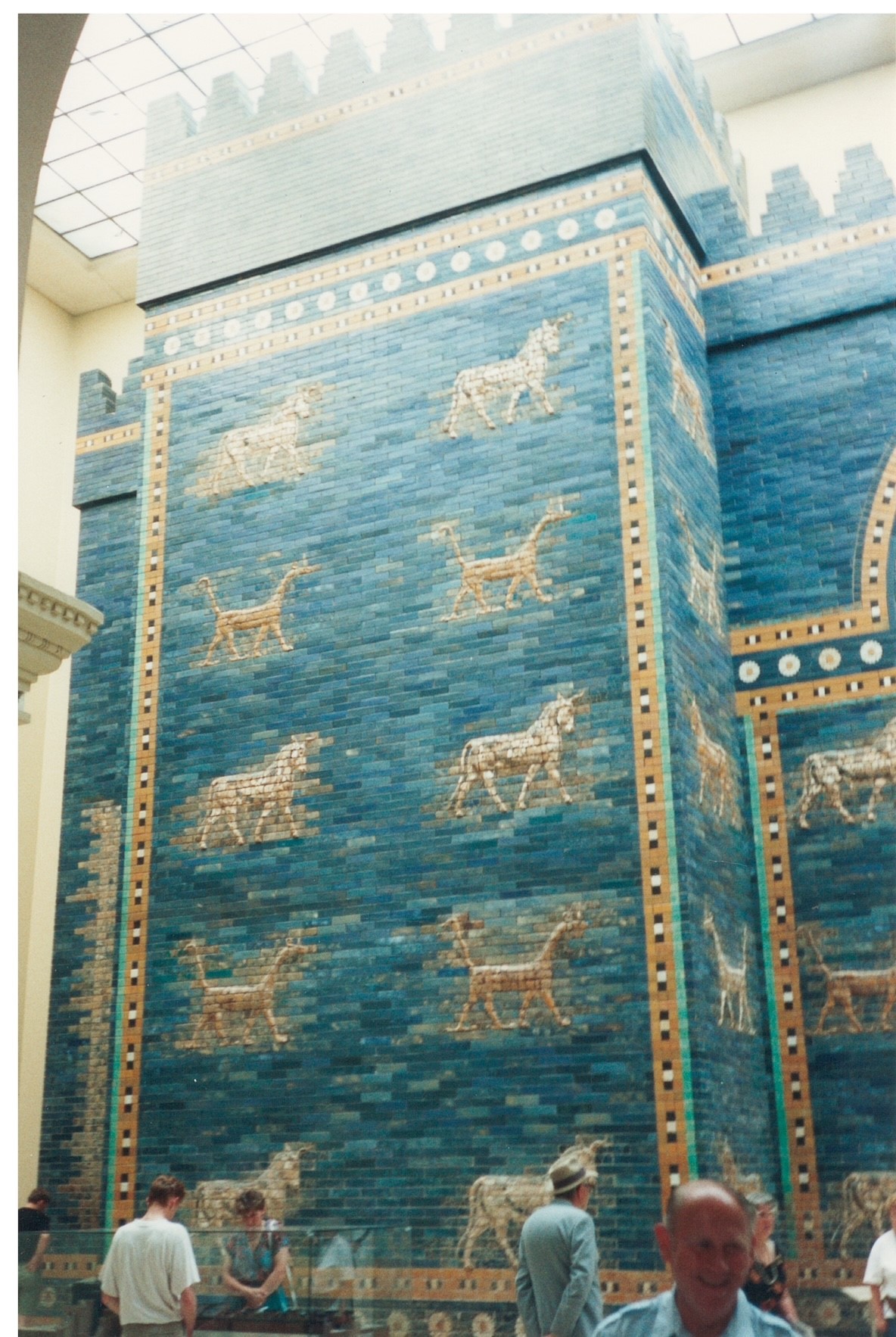

The Ishtar Gate and Pergammon Altar, © Nicholas M. O’Donnell (1996)

Why Germany has the Prussian blues

‘What do Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys have to do with Prussia?’ The German culture minister Claudia Roth asked the question in an interview that the federal government posted in December. And so a debate was launched about renaming the sprawling foundation that oversees 15 museum collections in Berlin and has more than 2,000 employees: the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (SPK), or Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. The question of whether one of the most important cultural institutions in the world should contain ‘Prussia’ in its name has stirred up controversies about colonialism, the origins of National Socialism, and the difference between acknowledging the past and honouring it. For many, Prussia is a byword for militarism, but in its heyday it was also one of the most important patrons and collectors of art.

Whether the term has any place in the 21st century is ultimately a political question for Germany. Yet as the decades’-long debate in the United States shows, there is a different between choosing to honour someone and pretending they never existed. No serious observer would suggest that a more inclusive name for this important institution is ‘erasing’ the history of Prussia, any more than removing a statute of Robert E. Lee does not mean the American Civil War never happened.

To most contemporary English speakers born after the Second World War, the name Prussia is an echo, an antiquated character from history lessons. When in The Simpsons, C. Montgomery Burns demands to be connected to ‘the Prussian consulate in Siam’, it was as a parody of the old world order.

Prussia was, in fact, the central character of European history in the post-Congress of Vienna era, the protagonist of proposals to unite the German-speaking kingdoms, duchies, landgraves and margraves that had formed the core of the Holy Roman Empire. Yet its origins could not have been more humble. In 1415 Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg granted the marshy plains that include present-day Berlin to Friedrich VI of the house of Hohenzollern the Mark of Brandenburg. In 1618 this was enlarged to include the eastern Duchy of Prussia (in what is now eastern Poland and the ancient seat of Prussia, Königsberg, which became Kaliningrad after the Second World War).

So lowly was Prussia that in 1701, Hohenzollern Elector Friedrich III of Brandenburg named himself King Friedrich I in – not of – Prussia for fear of offending the real power surrounding the lands of Brandenburg and Prussia: Poland and Augustus II the Strong, Elector of Saxony, who also held the title of King of Poland. It was his grandson, Friedrich the Great, who oversaw Prussia’s entrance on the international stage, but there is no question where Prussia’s real legacy lies, however: in the unification of Germany in 1871 under the Hohenzollern dynasty and the iron-fisted politics of Otto von Bismarck.

While that dynasty ended with abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1918, its association with militarism and authoritarianism did not. The appropriate connection between the German Reich leading up to the First World and the rise of Nazism thereafter is the subject of considerable historical debate. Uniquely among the constituent political entities that made up Germany, it was Prussia that was singled out for abolition – and not just by the victors. In a letter of December 1946, Konrad Adenauer, who would go on to be the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic, noted that Nazi Germany was ‘the consistent development of Prussian state way of thinking’. On 25 February 1947, an Allied decree dissolved Prussia as a state, declaring that it had ‘always been a carrier of militarism and reactionary acts in Germany’.

By the time of its abolition, the state of Prussia held a vast collection of cultural property including the Babylonian Ishtar Gate, Nefertiti’s bust, the Pergamon Altar and an unrivalled collection of Old Master paintings. (Also among its holdings: the Welfenschatz, or Guelph Treasure, which this author’s clients have claimed was a forced sale by Jewish art dealers to agents of Hermann Goering in litigation that went before the Supreme Court of the United States in 2020 and which is presently back in the lower courts).

The question of what to become of these collections remained and, in 1957, the SPK was created (in West Germany) to hold them. Strangely enough so soon after the abolition of Prussia itself, the foundation was given the defunct state’s name. As its current head Hermann Parzinger recently noted, even translating that name into other languages at conferences is problematic. ‘Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation’ comes close, although it should be something more like ‘Prussian Cultural Property Collection Foundation’. Neither exactly rolls off the tongue. Dr Parzinger, for his part, has indicated his approval of the idea of a name change

Claudia Roth’s comments come at an important period of transition in Germany. The previous culture minister, Monika Grütters, was in post for eight years and took a cautious and conservative approach to cultural policy. The new SPD-led coalition government includes the Green Party, of which Roth is a past co-chair. Change seems to be in the air: foreign minister Annalena Bärbock (another Green Party politician) recently proposed changing the name of the Bismarck Room in her ministry to the ‘German Unity Room’.

Roth raised two important points in her interview. First, should the name Prussia be the standard bearer for a cultural institution in the 21st century? (One would never expect a historical museum in Virginia to call itself the ‘Confederacy Heritage Museum’). Secondly, Roth noted that ‘Prussia is an important, but not the only, part of our heritage. Germany is much more.’ Her reference to Warhol makes the point: the collection’s origins before 1947 are clearly Prussian as a historical fact, but the considerable breadth of artefacts and programmes it has acquired then are not. Contemporary Germans might well feel excluded; imagine the reaction to referring to a foundation in Ottawa or Toronto as one of ‘New France’ based on its origins in 17th-century North American history.

Times have changed, and in no regard more than in attitudes to colonial legacies. Egypt would very much like Nefertiti back; Iraq has raised questions about the Ishtar Gate excavation; historian Götz Aly’s book The Magnificent Boat: How Germans Stole the Art Treasures of the South Seas connects a vessel (the so-called Luf Boat) in the SPK’s Ethnological Collection to what he terms a genocide in the South Pacific. The opening of the Humboldt Forum, which was meant to be the organisation’s crown jewel, has been criticised for displaying an outdated view of other cultures and for its association with far-right donors.

At the same time, the SPK has played an important leadership role in one the most high-profile cases of restitution: the return of Benin Bronzes. Is this a sea-change, or a distraction to deter harder questions about German occupation in Africa in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

Other members of that 19th-century German union are eyeing this development warily, too. ‘Will Bavaria be unnamed?’ asked a recent column in the Süddeutsche Zeitung. This has also prompted the inevitable arguments about ‘erasing history’. Ever willing to hurl a brick at the window, the tabloid Bild quoted a Hohenzollern descendant grumbling about who pays the SPK’s bills and historians asking if ‘maybe Martin Luther is next’.

Most English speakers may find this debate surprising. Germany has rightly (to an extent) been lauded for its willingness to confront its past. It seems strange that a country that will take responsibility for humanity’s darkest chapter equivocates about turning the page on an earlier era. There is no question, however, that the unease prompted by Roth’s suggestion is real. It will be fascinating to see where it leads.