There has been much discussion about the impact of the Presidential election on the art market, amidst much generalized anxiety about "fake news." What about "fake art?" Never one to be behind the curve, artist Richard Prince has stepped into the spotlight (to the extent he left). Declaring that one of his controversial “New Portraits” works of Instagram posts of others that was sold to Ivanka Trump is “fake” and that he “denounce[s]” it, Prince raises interesting questions about what the legal ramifications of such a repudiation might be. In this instance he has apparently refunded Ms. Trump’s money, but following on last year’s surprising Peter Doig trial (surprising that it got to trial, not that Mr. Doig won), a hypothetical artist making such a declaration might have some vulnerability under both common law, if not under the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990, 17 U.S.C. § 106A (VARA).

We have discussed Prince’s “New Portrait” series before, in which he reproduces an Instagram post by someone other than himself, and often adds a satirical comment below. Prince has been sued by multiple plaintiffs alleging copyright violations, which Prince has countered with the defense of fair use following on his victory in the prominent case by Patrick Cariou. We will not re-explore the fair use ramifications of Prince's art here, but it is a useful reminder that Prince is a skillful provocateur of expectations and norms, so his insertion into the topic of a divisive political election should not be a surprise.

As reported in various outlets, Prince made a work that consisted of an Instagram post by Ms. Trump with two hairdressers, which she then apparently bought herself as part of the “New Portraits” series. At the time, Prince noted that he had not been commissioned or asked by Ms. Trump to make the work, but rather “I found an image of her that looked like it was made up. It looked like the kind of thing I was interested in. . . . I don’t care who she is. I care more about who I think she is.”

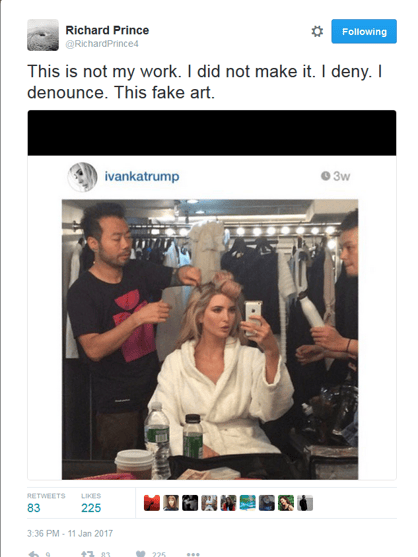

On January 11, 2017, however, Prince posted this to Twitter:

Thereafter in clarification, he posted “Not a prank. It was sold to IvankaTrump & I was paid 36k on 11/14/2014. The money has been returned. SheNowOwnsAfake” and “Redacting Ivanka's portrait was an honest choice between right and wrong. Right is art. Wrong is no art. The Trumps are no art.” Ms. Trump has apparently declined to comment.

If, as has been reported, Prince rescinded the sale and refunded the purchase price, then the buyer would probably have little additional recourse. But what if he hadn’t? Or if the original sale had not been as objectively verifiable in the market? Then a buyer might well be in a position to say that an artist had diminished the value of the artwork, value that is not necessarily limited to the purchase price. Recall the Doig trial. The plaintiff in that case got all the way to trial by alleging that Doig’s disavowal of the work in question was wrong on a theory of tortious interference, that is, the allegation that Doig was improperly interfering with the plaintiff’s economic interactions with others by denying the work’s authenticity. While I found it surprising that it made it to trial, particularly because an element of that claim is improper motive (not just the fact of interference/denial of authenticity), consider a hypothetical similar to what is happening here.

Imagine an artist who made a particular work of art. It is sold to a buyer in a non-public transaction, and the buyer retains the work in her home. When the buyer goes to sell it many years later (in particular after the artist has become more famous, and more expensive), the artist categorically denies it is his, and cites the buyer’s political beliefs as justification. Even if he returns the price, the work may by then be worth much more than she paid, and she may not be able to sell it as authentic depending on the phrasing of the denial. Could she then sue the artist for tortious interference? It seems that if Doig had to defend himself all the way to trial on the strength of allegations that were pretty thin, such a buyer might make some headway against an artist who was making an incorrect statement of fact. To be clear once again, this is purely hypothetical, but perhaps not far out of the realm of possibility. Art Market Monitor and others considered the potential impact on value that all this has, which is an economic rather than legal analysis, but would certainly inform the parties’ rights.

This is not entirely far-fetched, by the way. In addition to the Prince disavowal here, Gerhard Richter started implying a few years ago that he no longer considered his early works to be “his.”

Lastly, the always-astute Georgina Adam queried in response to the recent Prince story “This is interesting. If Prince can disavow a work under VARA , this would destroy its value I suppose...” Having thought about it, I think Prince’s VARA rights in this instances are limited. VARA’s right of attribution states that the artist has the right “to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of the work of visual art in the event of a distortion, mutilation, or other modification of the work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation.” Famously, Cady Noland successfully enjoined the sale of a work as a “Cady Noland” after it had been damaged to her dissatisfaction. I do not think it would apply here. First, the Prince work has not been “disort[ed], mutilate[ed], or other[wise] [] modif[ied].” Instead, it has been purchased by someone whom the artist wishes to criticize, which is certainly his right. Second, given that the statutory construction would be a stretch as applied to Prince, it must also be remembered that judges have strained to avoid strict applications of VARA, and it is hard to imagine that a politically-charged claim would be the instance in which that changes. One never knows, however.